by Sara Krauss

Although F. Scott Fitzgerald is most commonly praised for his accurate description of the American Jazz Age, his writing also reflects the immorality and aimlessness of the Lost Generation post World War I. Fitzgerald himself was an expatriate of the Lost Generation. According to William Byron, Fitzgerald’s “imagination [was] lastingly impressed by [World War I]” and the Lost Generation. He moved back and forth from America to Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, never settling in one city for long. Like many American men of the Lost Generation, he also became an alcoholic. Yet he did not seem to be ashamed by his affiliation with his fellow American expatriates. As Fitzgerald said himself, “‘The American in Paris is the best American’” (Byron 223).

Although F. Scott Fitzgerald is most commonly praised for his accurate description of the American Jazz Age, his writing also reflects the immorality and aimlessness of the Lost Generation post World War I. Fitzgerald himself was an expatriate of the Lost Generation. According to William Byron, Fitzgerald’s “imagination [was] lastingly impressed by [World War I]” and the Lost Generation. He moved back and forth from America to Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, never settling in one city for long. Like many American men of the Lost Generation, he also became an alcoholic. Yet he did not seem to be ashamed by his affiliation with his fellow American expatriates. As Fitzgerald said himself, “‘The American in Paris is the best American’” (Byron 223).

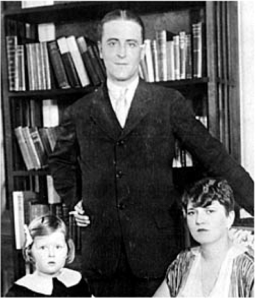

When Zelda and Fitzgerald discovered Zelda was pregnant in May 1921, they travelled to Europe in the first of their sporadic stays. During their stay at the Hotel de Saint-James et d’Albany in Paris, the outrageous partying couple caused quite a sensation. Fitzgerald left a pungent goatskin in their room, and Zelda tied the elevator to the gate on their floor with her belt, so she would never have to wait for it to arrive. They were kicked out of the hotel, and “found the City of Lights a bore and a disappointment because they knew no one there” (Mayfield 68).

Zelda and Fitzgerald returned to Europe in 1924. After a quick stay in Paris, they traveled to the French Riviera and lived in the Villa Marie in Valescure. Both Zelda and Fitzgerald enjoyed their time on the Riviera. Fitzgerald claimed it was the one place he was able to write as fluidly and creatively as he had when he had written This Side of Paradise as an unmarried young man. In July of 1924, however, Fitzgerald discovered that Zelda had been having an affair with Edouard Jozan, a young French aviator. As a result, Fitzgerald constantly questioned his masculinity and idolized men whose manliness was blatant, such as writer Ernest Hemingway.

In May 1925, while living in an apartment at 14 Rue de Tilsitt near the Arc de Triomphe, Fitzgerald met and befriended Ernest Hemingway at the Dingo American Bar and Restaurant. Fitzgerald considered Hemingway a writer with true talent and admired his masculinity. He claimed he was Hemingway’s mentor and helped him publish his work. Hemingway always resented Fitzgerald for his life of luxury, and their friendship eventually dissipated after Hemingway harshly critiqued Fitzgerald’s writing (Mayfield 93-94).

During their time on the French Riviera, the Fitzgeralds were introduced to Sara and Gerald Murphy, who later inspired the characters of Nicole and Dick Diver in Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night, to whom he dedicated the novel. It was at the Murphys home that Zelda attempted to kill herself. Zelda periodically checked in and out of mental institutions for the rest of her life. Her insanity had a profound effect on Fitzgerald, and despite his deep resentment of her affair with Jozan, he remained to be in love with her and struggled financially in order to give her the best medical care possible. His experience with Zelda’s insanity parallels the emotions and experiences of American expatriate Dick Diver in Tender Is the Night.

Increasingly prone to drunken behavior, Fitzgerald was often frustrated by his inability to write. When he was drunk he made outrageously inappropriate remarks. For instance, when he finally met Edith Wharton, whose writing he had long admired, he told her she needed to “live a little.” His offensive comment caused her to write later that he was “horrible” (Byron 199). Among his many other drunken escapades were his attempt to saw a bartender in half to see what was inside, and his night ride down the Champs Elysees on a tricycle, hitting doormen with a bread loaf. Sara Mayfield points out that both Zelda and Fitzgerald were “fast drifting into the emotional slum in which all too many expatriates ended up abroad – working too little, drinking too much…roaming aimlessly about Europe in search of some romantic paradise, lost with the first flush of their youth” (Mayfield 114).

Fitzgerald struggled with alcoholism and hypochondria for the rest of his life. Crushed under the pressure of providing for Zelda’s care in various mental institutions and his daughter Scotty’s education, Fitzgerald drank alcohol as an anesthesia when many of his novels and Hollywood movie scripts were rejected. He continued to write short stories to earn money, but was often in terrible debt. While living in Hollywood, Fitzgerald began writing the novel The Love of the Last Tycoon. At the age of forty-four, he died of a heart attack in the apartment of Hollywood columnist Sheilah Graham, with whom he was having an affair. The Love of the Last Tycoon remained unfinished at the time of his death, and critics claim it could have been his best novel if it had been completed.

Works Cited

Byron, William. F. Scott Fitzgerald, A Biography. Trans. Andre Le Vot. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1983. Print.

Gallo, Rose Adrienne. F. Scott Fitzgerald. USA: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., Inc., 1978. Print.

Graham, Sheilah. The Real F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thirty-Five Years Later. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, Inc., 1976. Print.

Hemingway, Ernest. A Moveable Feast. 1964. New York: Scribner, 2003. Print.

Mayfield, Sara. Exiles from Paradise, Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald. New York: Delacorte Press, 1971. Print.

Pingback: Party Like a Fitzgerald in Paris | Untapped Cities

Very informative article. I have read many biographies of Fitzgerald and they all allude to drinking as his downfall. Beginning at Princeton